USM Online offers rigorous undergraduate and graduate career-focused programs designed with your busy life in mind.

Online Undergraduate Programs

Our undergraduate programs are designed with flexibility in mind so you can jump-start your career and learn at the same time.

Degree Completion Programs

Returning to university after a break from school? Welcome back! Our online programs, degree completion tracks, and generous transfer policies make it possible for you to finish your degree and advance your career!

Online Graduate Programs

We offer a variety of Master’s and Doctoral programs 100% online, including Accelerated Master’s Programs with multiple start dates to earn your degree faster!

Frequently Asked Questions

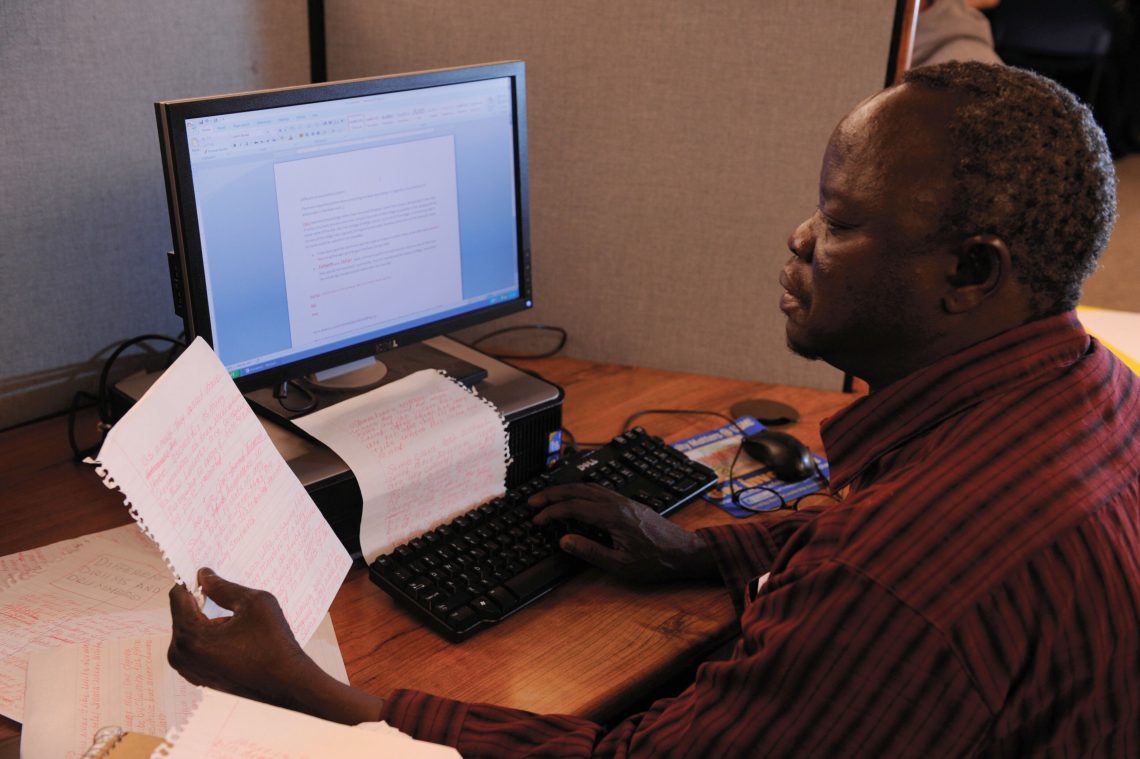

The Online Experience

Wonder what it’s like to get your degree online? Learn more about USM’s supportive community that’s designed to help you succeed.